What was the Rorke’s Drift Test?

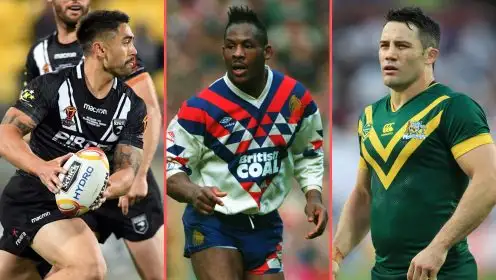

England will wear a special jersey when they face Australia in Melbourne this Sunday, commemorating a test match from a century ago. But just what was the Rorke’s Drift Test?

This historic match took place on July 2, 1914, and has attained legendary status in the sport. In many ways, the 14-6 victory of the Northern Union over Australia has come to be a metaphor for the values of courage, solidarity and the ability to face adversity that characterise our game.

The name for the game was coined as a tribute to the courage of the Northern Union players, with it being compared to the battle fought at Rorke’s Drift in the Zulu War in 1879, when British troops held a post in the face of overwhelming odds.

The circumstances leading up to the game were somewhat controversial, and helped set the tone for a classic ‘backs to the wall’ display by the Lions on foreign territory.

The Northern Union tourists had arrived in Australia at the end of May, 1914, and had played six warm-up games before taking on the Australians on June 27.

This game had been put back by a week after the tourists requested it. Although the hosts had acceded to that request, they refused to postpone the second test, meaning that the Lions faced Australia in the second test on June 29, just two days after the first.

This short turnaround meant that injuries began to bite, and the British management requested that the third test, scheduled for July 4, be postponed until the end of August.

The management team of St Helens’ Joe Houghton and Huddersfield’s John Clifford wanted the game played after the tourists returned from New Zealand, where they were scheduled to play after the Australian leg of the tour.

They also requested that the game be moved to Melbourne, well away from the rugby league hotbeds of New South Wales and Queensland.

The New South Wales Rugby League (NSWRL) refused to countenance these demands, and, with at least one eye on a forthcoming New Zealand All Black rugby union tour of Australia, insisted that the match be played as planned on July 4.

A later date for the game would see it receive a lower public profile, especially in Melbourne, with the rugby union tour competing for attention.

The NSWRL secretary, Ted Larkin, telegrammed the Northern Union hierarchy back in the North of England, to register a protest.

Although the perception by many at the time was that the NSWRL was trying to squeeze as much financial profit from the tour as possible by playing three Test Matches in nine days, they also wanted to ensure that rugby league did not lose any of its growing popularity by having to compete with union for attention.

An Australian Rules ‘carnival’ was also planned for August in Sydney, offering more distraction from the 13-man code.

The Northern Union hierarchy back in England were not unsympathetic to Larkin and the NSWRL’s point of view.

Indeed, an ‘unnamed forward’ in the British touring party told the Sydney Morning Herald that the Northern Union was: “Fully alive to the great possibilities of the 13-a-side code in NSW, and were not the men to sanction an action that would rob the Sydney public of witnessing the most important match of the tour.”

Joe Platt, the NU secretary, urged the British team to adapt to the circumstances and play with pride.

“We confidently anticipate that the best traditions of Northern Union football will be upheld by you,” he said.

“We hope that you will expend every atom of energy and skill you possess to secure victory; failing which, we hope you will lose like sportsmen.”

Houghton still disagreed with the decision, however, and it was left to his colleague John Clifford to put some fire in the player’s bellies.

“You are playing a game of football this afternoon but more than that you are playing for England, and more even than that, you are playing for right versus wrong,” he said.

“You will win because you have to win. Don’t forget that message from home. England expects every one of you to do his duty.”

The players, who included the great Harold Wagstaff amongst their number, apparently left the team meeting where those words were spoken in silence – their resolve and will to win welded into their souls.

“I was impressed and thrilled as never before or since by a speech,” recalled Wagstaff, two decades later.

The team which marched out from the tunnel at the Sydney Football Ground on July 4 saw five changes from the second test line-up from the previous Thursday.

Gwyn Thomas, Johnny Rogers, Bert Jenkins and Fred Longstaff, all first-choice players, were all missing. Alf Wood, who replaced Thomas at full-back, was playing with a badly broken nose.

Just after kick-off, the Lions’ Frank Williams suffered a knee problem. After limping around for most of the first half, he was forced to exit the action at half time.

Douglas Clark was also forced off in the second half, having broken his thumb and dislocated his shoulder.

He shed tears of frustration after he realised he was unable to continue.

But the Northern Union team thrived on the adversity, and dominated the game, even when reduced to 11 men.

They led led 9-0 at half-time, with Leeds’s Willie Davies bagging a try, and Oldham’s Alf Wood kicking three goals.

The Australians pushed hard against the Northern Union’s 11 men, but, despite now playing with five forwards and eight backs to the Lions’ seven backs and four forwards, could not break down heroic defence.

Widnes forward Chick Johnson grubber kicked and dribbled the ball to cross for the try which put England into a 14-0 lead, but then another player was forced off injured.

The Northern Union team were down to 10 men when Oldham’s Billy Hall was taken off with concussion. Australia took advantage to score two uncoverted tries to bring the score back to 14-6.

All 10 of the Northern Union’s remaining players fought hard until the final whistle to secure an unlikely win.

But it was Huddersfield’s Harold Wagstaff who really captured the hearts and minds of every spectator that day. The Sydney Morning Herald hailed his defence, with their correspondent writing: “He tackled with the tenacity of a grizzly bear.”

Australian captain Sid Deane recalled that: “Wagstaff was not only brilliant in attack and wonderful in defence but his leadership was a most important factor in the team’s success.”

Wagstaff himself told the press that: “It was the hardest game of my career.”

Rugby league had only been around for 19 years at that point in time, but already history had been made. The game secured international competition in the minds of the game’s supporters, and set a standard for bravery and commitment which persists to this day.

It is therefore fitting that England will be wearing tribute red-and-white hooped jerseys on Saturday to commeorate this great occasion.

Let’s hope that the spirit of Wagstaff, Johnson and the rest of those Northern Union heroes can be conjured in Melbourne by their modern-day successors on Saturday.