The Super League Revolution – Part 1

The turn of the century signalled the end of a decade which brought about a monumental shift in the sport’s direction. The 1990s will long be remembered in the game’s history as an era that oversaw the closing of one chapter and the opening of another, namely, the transition from winter to summer and the ditching of the Loiners, the Wire and Northern in favour of the Rhinos, the Wolves and the Bulls. Super League had arrived.

The advent of this new competition meant the sport left the 90s in a much healthier state than it had entered it. Crowds were up almost 50%, the standard of stadia had improved dramatically and Wigan’s trophy monopoly had been broken by the growing number of full-time professional clubs.

It wasn’t only the net increase in punters coming through our gates that the sport had to celebrate though, Bullmania and Cougarmania led the way in opening the sport up to a wider demographic than ever previously thought possible. For the first time in our great game’s history, women and children were now attending matches in their thousands and forcing clubs to re-evaluate their marketing philosophies or risk being left behind.

A stormy winter prior to the inaugural season of summer Super League had many long-standing supporters questioning the merits of Maurice Lindsay and News Corporation’s new competition. The famous Widnes club had been denied a place in the new division in favour of a new club from Paris and some of the sport’s other notable names like Salford, Swinton, Featherstone, Wakefield and Castleford were forced to contemplate merging with their local rivals to cement their future at the game’s highest level.

Sky Sports spearheaded many of these changes, hoping to create a more far-reaching competition and extinguish the tired image of Rugby League as a working man’s game played on the M62 corridor. There was talk of Scottish, Irish, Welsh and even Spanish clubs taking their place among the game’s more unfashionable and longer established sides which sparked feelings of excitement and outrage depending on who you spoke to.

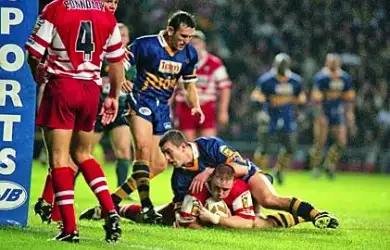

It was one of the old guard that clinched the inaugural Super League trophy though with Wigan finishing top of the division on points. For the first time in eight years, however, the Challenge Cup had a new name on it. St. Helens triumphed over the exciting Bradford Bulls in a record breaking final with 72 points scored and a hat-trick for prodigal 19-year-old Kiwi Robbie Paul. His side may have lost but we had certainly not heard the last of Robbie and the Bulls.

Workington, hoped by many to provide a cornerstone from which Cumbrian rugby league could thrive, had a disastrous campaign, winning just two just two games all season. Their tired old ground and dwindling attendances did not fit in with the sport’s new vision and the men from Derwent Park were relegated.

The new Paris club, playing out of the famous old Charlety Stadium, competed admirably in their first ever season but ultimately finished 11th, one place above Workington. The highlight of the year was an inspirational win over Sheffield Eagles in front of over 17,000 people in what was the club’s first ever competitive match. Hope faded though and attendances dropped dramatically when the wins stopped coming. More worryingly, the smattering of Australian talent brought in to compliment and develop the French contingent now formed the backbone of the team. Just 500 people watched PSG host Salford the season after and the club was eventually wound up and is looked back on today as a major failure.

The plight of Paris and Wokington and the bleak picture it paints of the sport following its dramatic U-turn does not, however, tell the whole story.

Back in Bradford, business was booming. On the pitch, the Bulls had a side sweeping all before them, winning all but one Super League game to clinch the ’97 title at a canter. It was off the pitch though where the big changes were taking place. Bull-man and Bull-boy were moon-walking and quad-biking their way into young supporters’ hearts after ticket giveaways along with school and city-wide promotions had made the Odsal bowl the place to be on matchdays.

All around the Super League, half-time flasks of Bovril had been replaced with ice cold cans of beer and pop. Flags and banners were now a mainstay on the terrace and face-painted children with drums along with in-play brass bands had turned matches from a scrap in the freezing mud to a party the whole family were invited to.

The introduction of the ‘video ref’ to televised games had brought with it controversy, uncertainty and sensationalism. It was an instant hit. There are few things in modern sport that can match the excitement of ‘the square in the air’ with the outcome of a game resting on a decision flashed up on a ten-foot square monitor. Critics of the ‘big screen’ claim it delays the action unnecessarily and takes responsibility away from referees. What cannot be ignored though is the pageantry it brings and the talking points it creates – Those worried that this technology would sanitise the sport by removing all doubt were way off. The man in the television truck, it would appear, gets it wrong as often as the man on the pitch does, much to the delight of the commentary teams.