Jamie Jones-Buchanan: I’ve loved, lived and learned, now I need to leave a legacy

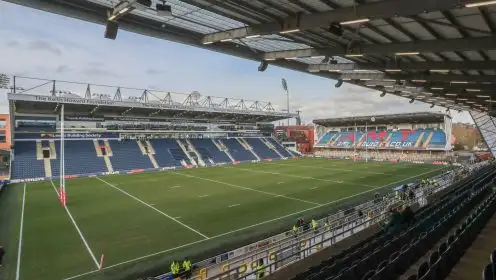

Jamie Jones-Buchanan bounds around the corner of the cafe at Emerald Headingley Stadium, finds me sitting alone at a table, and bellows that noise normally reserved for a bartender who has just dropped a pint glass: “WAHEYYYY!” I’ve never met Jones-Buchanan before, but I already know this is going to be a lot of fun.

Interviewing the veteran Leeds Rhinos forward is like speaking to no other sportsman. Over the course of our conversation we chat about Carl Jung, Socrates, Stephen Covey, Jordan Peterson, Brexit and Donald Trump. He references scientific studies, Christian proverbs, Plantagenet Kings and the biological make-up of lobsters. He tells one story about how his favourite colour changed from red to blue after giving up tea and coffee for Lent, which I’m not sure what to do with but nonetheless feels quite important just by the way he tells it.

“I’ve always been quite an extroverted person,” he laughs. “I’ll always try and break the trends and start new ideas off. I sometimes get laughed at. I’m one of these, me, I’m not really shy or worried or bothered by what people think about me.”

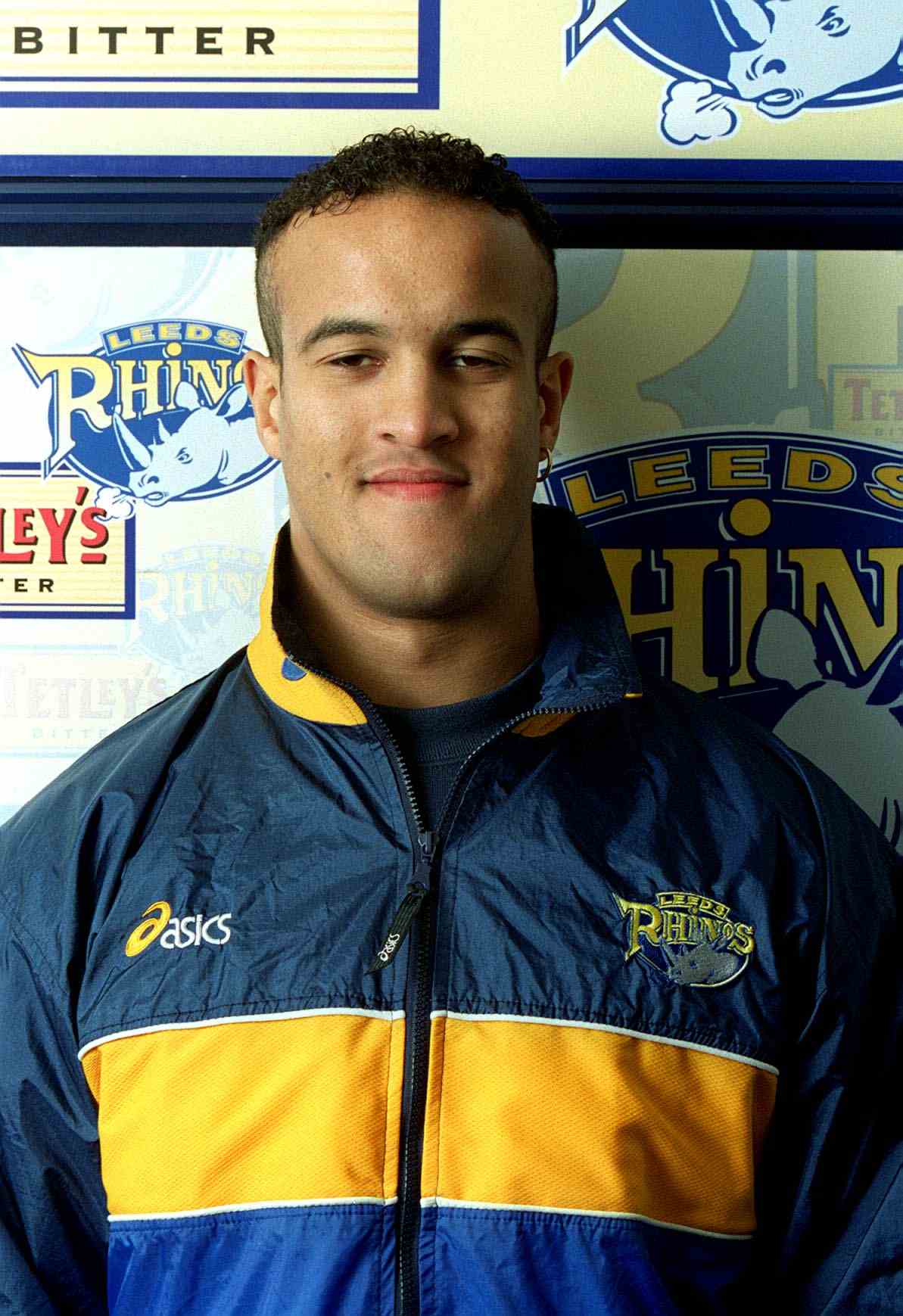

While a few grey hairs can be found nestling among his trademark bushy beard, on the eve of his twentieth and final season as a professional rugby league player – all of which have been spent with his hometown club – Jones-Buchanan remains a relentless bundle of energy and enthusiasm.

But the 37-year-old veteran finds himself in a unique position: despite over 400 games under his belt and enough Grand Final winners’ rings to leave just his thumbs free, Jones-Buchanan needs to prove himself to a new coach, Dave Furner, a man he once called a teammate 15 years ago.

For the first time since 2006, Jones-Buchanan will be wearing a squad number other than 11. Part of that is down to symbolism; the number 20 he will now wear across his back a sign of his remarkable longevity. But it is also a reminder he is no longer certain of a place in the team. Trent Merrin, an Australia international and NRL Grand Final winner, has arrived as one of two marquee players signed by Leeds during the off-season and has taken the number 11 worn with such distinction by the boy from Bramley over the past decade.

While it will no doubt feel strange for many onlookers, for Jones-Buchanan it is familiar territory. Ever since his school days he has relished proving doubters wrong, reinventing himself on a number of occasions along the way.

“Race never came into it really,” he says, “but I always knew being mixed race in a predominantly white school brings about its own dynamic. Making friends is really important. We’re a communal species and we don’t do well on our own. I knew that when I did something extraordinarily well people would go ‘wow!’ and almost exalt me.

“Some kids would pick on me, whether it be in the street or the classroom. They’d say mean things or not treat me very well. Then when it came to playing sport against them, I didn’t have to beat them, I could destroy them, embarrass them and make them look little, legally and fairly, just by being that much better at sport.”

Aside from nine months in Scotland while his step-dad worked on submarines in the Navy, Jones-Buchanan has lived in west Leeds all his life. He refers to Bramley as “the Big Apple”. “I still live there and I’ll probably die there,” he cheerfully ponders.

“My upbringing was quite interesting. My mum had me when she was 18. My biological dad left when I was about two – my mum kicked him out. My dad was quite notorious, a lot of people knew him in and around Bramley and west Leeds. He was a doorman at an old nightclub called Barcelona. He went on to have 11 kids, I was the oldest, to about five different women.

“I had everything I needed in life, a loving childhood and loads of opportunities. Average kid in and around school. I think when you grow up you don’t really understand what poverty is, you just live in the environment you’re in. It’s all relative.

“My parents and family were always really proud. They were proud workers. When I grew up I probably took on this mantra as well. You had to work hard and have a great work ethic and pin your shoulders back.”

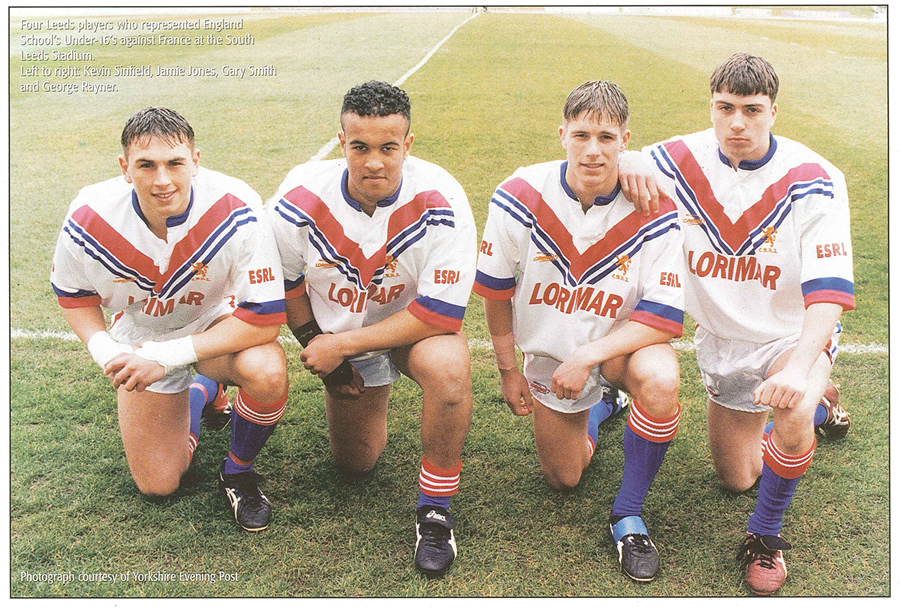

Bigger, stronger and more athletic than his peers, Jones-Buchanan joined Leeds’ academy system at the age of 15. As a child he had stood on the South Stand at Headingley idolising the likes of Graham Holroyd and Garry Schofield, but he never even considered the possibility of one day turning out for the team.

“Then when I signed for Leeds I thought, ‘ Why not? Let’s try get in the first team.’ Here I am, four hundred and twenty odd games later.”

His longevity is remarkable in many ways, most of all because his career was almost over just as it threatened to take off. Having made his debut against Wakefield in 1999 – “I just remember flipping getting smashed by Jamie Field. I only had half of my name on my shirt which was a bit disappointing because I thought there’s going to be half my family upset here” – a serious injury very nearly led to that being his only appearance for the Rhinos.

After breaking his jaw in a second team game against Wigan, he continued to train “squatting ridiculous weights, more than I lift now, 200kgs” when he felt his groin become sore. By the time he drove back to Bramley, he couldn’t even get out of his car.

“I’d gone through my childhood injury free. I remember saying, ‘I don’t do injuries,’ and I wish I hadn’t because it has come back to haunt me. Long story short, I pulled my adductor off the groin and pulled the bone off with it. My pelvis had basically come away from my hip joint. I was a mess.”

It took the best part of two years to recover, by which time younger players such as Danny McGuire, Rob Burrow and Chev Walker had overtaken Jones-Buchanan and began to make an impact in the first team. Leeds’ medical staff even suggested to Gary Hetherington that Jones-Buchanan was finished, but the Rhinos chief executive gave the youngster an extended period to prove he could still cut it.

“It would have killed me off. By God’s grace I got through it. I had to reinvent myself because I’ve never been as quick or as agile as I was back then. A fair bit of my game went. I evolved into somebody who’s a hard worker, a grafter in the middle, and that’s how I survived it.

“There’s a biblical proverb, proverb 17: ‘A crucible for silver and a furnace for gold, but the Lord is the tester of hearts.’

“What it means to me is you get a precious metal out of the ground, silver or gold. It’s not pure, you have to put it in a crucible or a furnace to refine it. Melt it down, high heat, high pressure. What comes out is refined gold.

“Gold and silver are amazing. Silver is the best electrical conductor there is and gold is this highly unentropic substance which is very hard to break down and tarnish. It lasts forever nearly.

“For us as human beings it’s our hearts that get put in those refining fires when we get hurt either physically or emotionally. If we have the strength to persevere – strength in God for me – and strength in the people we surround ourselves with…when we’ve got that network around us we can come through anything.

“When you do come through you’re refined for it. I’ve always called it the refining fire. I’ve been through a few and I’m still going through some now. But I know that at the other end I’ll come out better for it.”

Midway through our interview, two young Leeds fans walk through the cafe clutching carrier bags containing brand new kits for the 2019 season. Upon spotting Jones-Buchanan deep in conversation, one of the girls exclaims: “Look, it’s Jamie!” As if he already doesn’t look distinctive enough, adorning the wall by which we’re sat is a huge poster of Jones-Buchanan celebrating Leeds’ 2011 Grand Final triumph. “Hiya, y’orite?” he cheerfully waves as the supporters nervously giggle their way past.

While he continues to insist there has never been a point when he has felt fully established at Leeds, the posters – and the trophy cabinet – are a reminder of the legacy which Jones-Buchanan has helped forge as part of the club’s ‘Golden Generation’.

It is a far cry from the Leeds team which he grew up supporting: an expensively-assembled group of individuals with big egos who continually under achieved.

“I’ve got eight grand final rings, I played in seven of those, and one of my favourite ones and probably the one that I’ve worn the most is 2004, the first one. It was the first time in my lifetime that Leeds RL had won the championship.

“I’d grown up here watching Ellery Hanley and Schoey – I could name the full side from that early to mid-90s era. They never won anything, it was terrible. The first time I saw Leeds win it I was there on the pitch playing. That was a real special thing.”

But after ending their 32-year wait for a title, Leeds have never done it easy. After winning the World Club Challenge the following year, they finished 2005 as runners-up in every domestic competition. An underwhelming 2006 passed by with dispiriting defeats to lesser-fancied teams the Challenge Cup and play-offs.

The Rhinos have never made good favourites but have always relished being underdogs. Of their eight Grand Final successes, they only travelled to Old Trafford as favourites twice. Instead they ended 2007 upsetting a St Helens side everybody expected to win a second successive Treble, with Jones-Buchanan scoring Leeds’ final try by pinballing his way to the line after a series of outrageous offloads.

“There’s a picture from that game, it’s my favourite picture. Gaz Ellis is stood side on. That was the first year I grew my beard. I was young and had hair and look like a flipping spartan. Kirkey is picking somebody up off the floor and it just looks like a war. That was also the first time we had a kit as dark as that and it was just intimidating.”

Jones-Buchanan often compares rugby league to combat, and he speaks eloquently and articulately about his worry that the game is becoming sanitised. It’s hard not to think back to one of his finest moments in a Leeds shirt, which came during a World Club Challenge clash with Melbourne Storm at an Elland Road stadium consumed by its own microclimate of howling winds and horizontal rain.

The turning point came 10 minutes before half-time, with Leeds trailing 4-2. Watch it back now and try not to laugh as Stevo suggests the Rhinos are getting “battered” seconds before Storm winger Steve Turner returns a long kick downfield from Rob Burrow by sidestepping into Jones-Buchanan’s left shoulder and is stunned to the floor with a hit so ferocious it would make Chuck Norris wince.

“If I’d have done that now I’d probably get banned for three or four games for doing it. It was one of my favourite parts of my career, if not favourite. It just needed something to lift the game.

“Growing up in Leeds I always had this recurring dream of playing for Leeds Rhinos and Leeds United,” he says, unzipping his bodywarmer to reveal he’s wearing a Leeds United jumper. “I remember after that shot the Revie Stand celebrated as if somebody had scored a goal. Everybody just lifted.”

Shortly after that tackle, Leeds, playing with a surge of adrenaline, worked the ball out wide for Scott Donald to score and went on to win 11-4.

“We look back on that and we beat the mighty Melbourne Storm. We bashed them mate! And on, for me, an amazing stage. Second best only to Headingley. It was an amazing moment, but I suppose that has been removed now.

“Some of the oldest sports in humankind are gladiatorial sports, combat sports – boxing, the Colosseum – that’s been a big part of who we are for as long as our history.

“As far as the game is concerned we’ve got to understand that rugby league is a gladiatorial game. That is a big selling point, it’s a big USP. If we’re going to take that out then we lose that attraction. Which is fine, if you want to make it a skill sport and a fast sport that’s fine. But you’ve got to understand that a massive degree of people just aren’t interested any more because it’s not a gladiatorial game.

“There should be penalties for getting some things wrong. If you go for a shoulder charge and get it wrong and break somebody’s jaw you should face consequences. But I think we all go out there understanding, certainly when I first started playing the game and in my early career at Leeds, this was all part of rugby league and we all took to that pitch with complete acceptance of the risks.”

We don’t like to talk about it in rugby league. We like to focus on the skill and the speed which sets the game apart from similar contact sports. But at the end of the day, sometimes a match is won or lost according to which side has gone out and hurt their opposition the most. It’s something Jones-Buchanan has been thinking about a lot recently.

In 2017, he was part of the team which made the film As Good As It Gets, a feature-length documentary looking back at this period of unprecedented success for the Rhinos, culminating in their historic Treble of 2015.

Jones-Buchanan is at the centre of some of the film’s most poignant moments: his admission that he visited former coach Brian McDermott in the midst of a period when his body was struggling to cope with the rigours of the game and broke down “bawling my eyes out”, worrying yet again that he was finished as a player; the image of his grandma pushing her way through the St Helens dugout to check on her grandson as he was stretchered off the field in a Challenge Cup semi-final with another career-threatening injury; the pride with which he speaks about the moment Kevin Sinfield, his best friend in the game, invited him to lift the Challenge Cup trophy with his leg in a brace having missed the final.

But Jones-Buchanan has been thinking a lot recently about something Jamie Peacock mentions in the film. Peacock, as Jones-Buchanan likes to say, is the “Alexander the Great of rugby league”. A player who defied all logic of human physiology to become the most decorated player in Super League history.

And yet Peacock himself almost quit the game ahead of 2015. Sixteen years of wilful neglect for his own personal safety in order to get the better of his opponents had left his body in near constant physical pain. Feeling older and wise, the thought of taking to the field for another year and being “nasty” seemed “stupid”.

“That was the first time I ever saw JP say anything like that. It was just like, ‘Wow, he is human!’ He’s not some robot or demagogue like we perceived him to be.”

Now 37 himself, the age at which Peacock eventually retired, those words have become prescient for Jones-Buchanan, who has remarkably few obvious battle scars other than a disfigured knuckle on the ring finger of his right hand.

“You imagine that for all my life since I was nine years old playing rugby league every week, and certainly from being a professional from being 15, I’ve just been surrounded by alpha males. There’s this indoctrinated idea ingrained within you that you can’t be soft, you can’t be somebody who backs down, and you’ve just got to keep carrying that pigskin in regardless of what it does to your body.

“But it does hurt. And when you’re 37 years old you start getting arthritic joints. Entropy starts to affect you, things are breaking down. I don’t recover as quick, I’m not as fast or agile or co-ordinated as I was when I was 27, so these are all things that you’ve got to manage.

“I’m lucky as a forward in rugby league that you can see that less. Somebody like Andy Murray, if his hips are knackered then that quarter of a second is a million miles away from him. A quarter of a second in rugby league you don’t notice that much as long as you’re willing to keep getting hurt.

“Yes I sometimes think, ‘Flipping heck, do I want to come in on a Monday morning and wrestle an 18-year-old Mikolaj Oledzki who wants to just take me head off and take my position?’ There will come a relief from that when I retire but I’ve got at least eight or nine months left of the desire to keep winning and be successful.”

But Jones-Buchanan is still not quite ready to look too far into the future just yet. Appointed media manager for the England Knights tour to Papua New Guinea in the off-season saw him in the unusual position of being sat on the staff table across from players he still considers teammates with Leeds, but he loved the opportunity to help spread the gospel of rugby league in much the same vein with which he uses the YouTube channel and TV show Rugby AM, which he established with his friend Alex Simmons in 2012.

Just before we finish up, Jones-Buchanan shows me the background on his phone. It’s a picture of his four children modelling the new Leeds kit. His work at Headingley is not yet over.

One of the first members of Leeds’ ‘Golden Generation’ will be the last man standing as a new-look Rhinos side aims to bounce back from the disappointment of a second bottom four finish in three years in what has been a turbulent few seasons since the zenith was reached with the Treble.

“[That season] typified the culture and the camaraderie and the belief in the group. It was only won by this much because the lads worked so hard and were sacrificial.

“I missed out on all those big moments because of the quad tear in the semi-final. It exemplified Kevin Sinfield’s character and the way that he led the team when he took me up to lift the Challenge Cup with him. Even though I wasn’t playing and I wasn’t fit I wasn’t forsaken either. Out of adversity is born a real message of hope and meaning behind what it means to be a Leeds Rhinos player.

“I don’t mind you saying this: what’s important to me in this last year is trying to communicate that to the players here. It’s really easy to tell a person and tell a group and for them to say, ‘Oh yeah, I get that.’ But to actually live it is a completely different story. That’s what I need to do by example to try keep that ethos alive.

“There’s that Stephen Covey quote about life and business being to love, to live, to learn and to leave a legacy. I’ve done the first three pretty much over the course of my career, and I’m still doing it to a degree. But I’ve got to that age where it’s time to leave a bit of a story and a legacy to everybody else.”